|

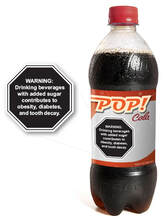

If you browse a supermarket aisle in Chile, you’ll notice something different about the candy bars, sodas, and potato chips – these and other unhealthy foods are likely to display one or more stop sign logos on their packaging, warning you about high levels of sugar, salt, fat, or calories. Since 2016, Chile has required these warning labels on the front of any product with higher-than-recommended levels of these nutrients. The country required these warnings as part of a suite of policies meant to curb obesity and other diseases linked to poor diet. Following Chile’s lead, five other countries have passed food and beverage warning policies. In the U.S., lawmakers in five states have also proposed warning labels that would apply specifically to soda and other sugary drinks. New research is emerging that could help policymakers design these warning labels to maximize their impact. One key question is whether warnings should focus on nutrients or on potential health harms. In Chile and other Latin American countries, sodas and other sugary drinks display labels that read, “Alto en azúcares” (“high in sugars”). In contrast, U.S. proposals focus on the health harms of these beverages. For example, California's proposed warning would read: “STATE OF CALIFORNIA WARNING: Drinking beverages with added sugar(s) may contribute to obesity, Type 2 diabetes, and tooth decay”. In a study published earlier this year in Preventive Medicine, our team found that both types of warnings – those focused on nutrients like sugar or on health harms like tooth decay – are perceived as effective by consumers. Surprisingly, warnings that described both health harms and nutrients performed no better than warnings that only described health harms. Because longer warnings can be harder to read, policymakers may want warnings to focus on health harm or nutrients, but not both in combination.

Other tweaks to warnings’ design may also boost their effectiveness. For example, our team published another study in American Journal of Public Health, finding that warnings with stronger statements linking products and health harms are more effective than those with weaker causal statements. In this study, participants viewed a variety of warnings on sugary drinks, cigarettes, and alcohol. They rated warnings that used stronger causal language (e.g., “causes” or “contributes to”) as more effective than those with weaker statements of causality (e.g., “may contribute to.”). Participants also preferred the stronger language, identifying these as their “most supported” language for product warning. This research suggests policymakers should consider designing warnings to use the strongest causal language justified by scientific evidence. A skeptic might wonder whether even well-designed warnings are likely to be noticed by consumers, much less influence their purchases. Yet evidence is emerging that food and beverage warnings can attract consumers’ attention and encourage them to make healthier purchases. For example, a randomized trial of more than 3,500 Canadian adolescents and adults found that placing nutrient warnings on products high in sugar, salt, saturated fat, or calories reduced purchases of these nutrients. Another randomized trial of 400 adults in North Carolina found that sugary drink warnings similar to those proposed in California reduced purchases of these beverages by more than 20%. Notwithstanding the potential benefits, controversy awaits, as with many nutrition policies, and U.S. warning policies will likely face legal challenges. For example, the City of San Francisco passed an ordinance requiring warnings on sugary drink advertisements in the city, but the courts struck down the requirement, finding that the required warning size (20% of the advertisement) likely violated the First Amendment rights of beverage advertisers. However, legal experts have argued that both scientific evidence and First Amendment case law support sugary drink warning policies. Additional research on food and beverage warnings will help lawmakers design warning policies that are likely to improve population health and withstand legal challenges.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

©2017 WeighingInBlog. All rights reserved. 401 Park Drive, Boston, MA

RSS Feed

RSS Feed