“Are there nuts in that?” was a phrase that I heard over and over again throughout my childhood. My best friend (and current roommate) is allergic to peanuts, tree nuts like walnuts and almonds, and soy. She thinks about and questions every bite of food before it is deemed safe. She finds going out to eat, which for most people is a fun and relaxing social activity, to be frustratingly limiting at best and dangerous at worst. More people now know someone with a food allergy, but are we aware of the mental burden of chronic food avoidance and fear? Studies have shown that kids with a nut allergy generally have lower emotional, social, and psychosocial quality of life than their non-allergic peers. Having to always say no—“No, I can’t sit with you at lunch”, “No, I can’t have a birthday cupcake”—can be socially isolating and embarrassing for allergic kids. It’s not all bad news, though; kids with allergies report less anxiety than others, with allergic girls reporting higher levels of anxiety than allergic boys. Kids also seem to grow out of some of the negative psychological side effects of allergies. As allergic kids get older and learn how to independently manage their allergy, they report higher quality of life.

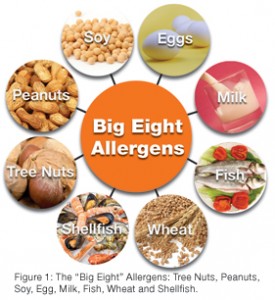

So what about the caregivers of allergic children? Numerous studies have shown that caregivers are significantly affected by their child’s allergies. Mothers of allergic children report higher anxiety levels than mothers of non-allergic children. Interestingly, they do not report feeling more stressed out than other mothers. Researchers at the University of Michigan Food Allergy Center dug a little deeper into the specific allergy-related risk factors. They found that reaction perception, food allergen type, and number of allergies diagnosed all influence caregivers’ anxiety levels and psychological well-being. Caregivers who are unable to correctly gauge the severity of their child’s allergic reaction have higher levels of anxiety and lower quality of life in several domains. They doubt their own ability to help their child in the event of an allergic reaction, and struggle to trust others to do so. Caregivers dealing with peanut and tree nut allergies report a higher quality of life than those whose children have egg or milk allergies, possibly because eggs and milk are generally harder to avoid and detect than nuts. And caregivers whose children have more than one allergy struggle more, reporting lower quality of life across all domains. There are ways to decrease the mental burden of food allergies. Having a treatment plan has a positive impact on both caregiver and child anxiety and quality of life. Having an epinephrine auto-injector (‘epipen’), which can quickly reverse an anaphylactic allergic reaction, was found to effectively lower allergy-related anxiety in both caregivers and kids. Interestingly, it didn’t matter whether allergic kids actually carried the epipens; simply being prescribed one had a significant impact. Another way to improve quality of life may be to let allergic kids eat the foods that “may contain” the ingredient to which they’re allergic. Although some minimal risk is involved, doing so makes kids happier because they can eat a wider array of foods, and requires less vigilance from caregivers. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, educating the caregivers and families of allergic kids can reduce anxiety and lead to a better, more peaceful life. And who doesn’t want that?

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

©2017 WeighingInBlog. All rights reserved. 401 Park Drive, Boston, MA

RSS Feed

RSS Feed